Music and Meaning: Spirituals at the Tampa Bay Casino

An ensemble of the UT Chorus performs "In Bright Mansions," as arranged by K. Lee Scott. Dr. Rodney Shores conducts. (Videographer: Troy Cusson)

SYNOPSIS

No one knows when “In Bright Mansions” came into existence. Created by slaves, the song evolved over time. A version of the spiritual appeared in print in 1867 as part of the anthology

Slave Songs of the United States, edited by Charles Picard Ware and others. This rendition included only the words and the melody. Harmonies continued to be improvised, and, over the next several decades, there were as many iterations of "In Bright Mansions" as there were African American church congregations who sang it.

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON AND THE POLITICS OF MUSIC IN TAMPA

Booker T. Washington and Touring Party in Daytona Orange Grove, Annual Edition of the Florida Sentinel, 1912

Booker T. Washington and Touring Party in Daytona Orange Grove, Annual Edition of the Florida Sentinel, 1912

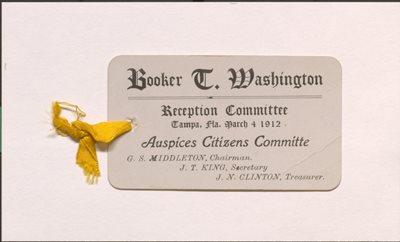

In 1912, educator and activist Booker T. Washington embarked on a speaker tour of Florida, sponsored by the state branch of the National Negro Business League. The tour included stops in Pensacola, Tallahassee, Ocala, Tampa, Lakeland, Orlando, Palatka, Daytona, and Jacksonville. At Washington’s request, black community leaders in each location created committees to plan his visit and accommodate his traveling party of educators, physicians, ministers, and business leaders. In Tampa, the committee headed by postal carrier George S. Middleton rented the Tampa Bay Casino for Washington’s speech.

Reception Committee Badge, Booker T. Washington Papers, Library of Congress

Reception Committee Badge, Booker T. Washington Papers, Library of Congress

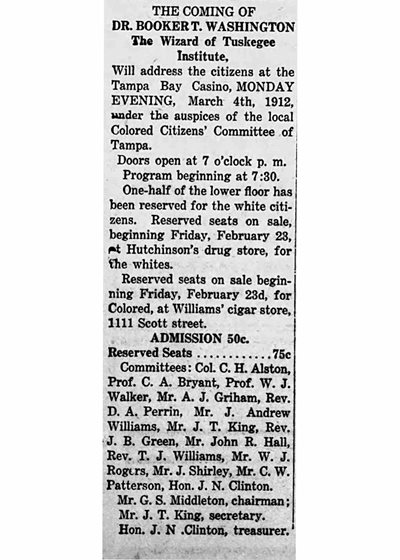

Opened by the Tampa Bay Hotel in 1896 as an entertainment venue, the Casino was acquired by the city when it purchased the hotel from Henry Plant’s estate in 1904. Middleton’s reception committee petitioned the city council to use the Casino for Washington’s speech, an act that asserted the inclusion of black citizens in Tampa’s public sphere. At the time, new local and state laws were contracting that sphere by eliminating voting rights and segregating streetcars. Unfortunately, the committee’s rental of the Casino required adhering to strict racial regulations. Black and white residents purchased tickets to Washington’s speech in separate locations, and the auditorium had segregated seating.

Tampa Times, February 24, 1912

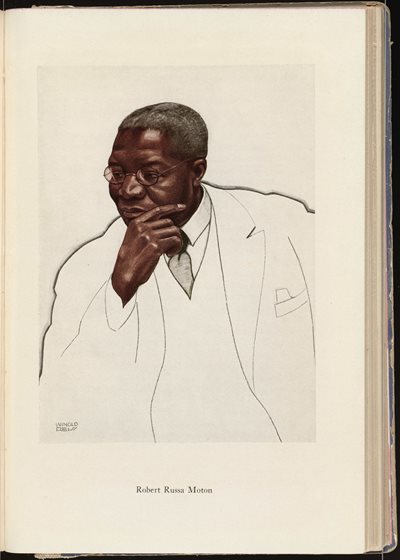

Music featured prominently in the program that Booker T. Washington and his traveling party presented at the Tampa Bay Casino on March 4, 1912. Robert Russa Moton, commandant of cadets at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, led the black section of the audience in singing two spirituals, “In Bright Mansions” and “Until I Reach My Home.” A quartet of local young men followed, performing a selection of traditional songs.

Winhold Reiss, Portrait of R. R. Moton, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Churches furnished the building blocks of black communities, and their cultural practices influenced most forms of association. The first African American churches in Tampa, such as Beulah Baptist (established in 1865) and St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church (established in 1870), provided much more than religious fellowship; they furnished political meeting space, schooling, job referrals, and social services. Practices that structured worship, such as collective call and response, carried over into all these domains, even after the creation of secular organizations. Audience participation, especially the singing of spirituals, made perfect sense to the African Americans who gathered at the Casino to hear Washington speak.

St. Paul’s AME Church, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library

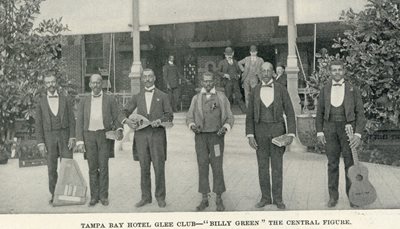

In contrast, whites found the sound of collective black voices singing “In Bright Mansions” and “Until I Reach My Home” to be remarkable. Newspaper articles gave disproportionate attention to the musical section of Washington’s program, which they characterized as “plantation melodies.” The accounts were steeped in a romanticized remembrance of the Old South that became popular during Jim Crow segregation. Images of happy slaves singing and working in unison commonly expressed this white racial fantasy. The Tampa Bay Hotel had already packaged a version of plantation memory for northern tourists’ consumption, replete with minstrel performances by black workers. During Washington’s visit, the Casino’s black and white audiences listened to the same spirituals, but they had very different interpretations of what they heard.

Leslie’s Weekly, April 7, 1898, p. 214.

POSTSCRIPT: THE FISK SINGERS, THE NEW NEGRO MOVEMENT, AND THE TAMPA BAY HOTEL

.jpg.aspx;?width=400&height=299)

Fisk University Jubilee Singers, 1875, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Over time, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers contributed to more respectful representations of black music in popular culture. In 1871, the student chorus who became known as the Jubilee Singers performed spirituals in concert halls and white churches to raise revenue for their school. Their repertoire included "In Bright Mansions." As a concert spiritual, the song acquired a formal arrangement. Although beautiful, this fixed structure sacrificed the more creative and improvisational elements that guided freeform singing in African American churches. For several years, their tours enjoyed tremendous popularity in the United States and Europe. Beginning in 1909, Victor Talking Machine Company recorded the group, distributing their songs as “folk music.” In the 1920s, leading black intellectuals and artists of the New Negro movement, including Alain Locke and James Weldon Johnson, championed spirituals as the country’s most original form of musical expression. Notably, Locke had been part of Booker T. Washington’s entourage in Tampa in 1912.

The Spirituals are really the most characteristic product of the race genius in America. But the very elements which make them uniquely expressive of the Negro make them at the same time deeply representative of the soil that produced them.

The above quote is from Alain Locke, ed., The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), page 199

The Fisk University Jubilee Singers appeared at the Tampa Bay Casino and the Music Room of the Tampa Bay Hotel on several occasions in the 1920s. Painter Winold Reiss created some of their tour posters in this period, another indication that the singers had been embraced by the leaders of the Harlem Renaissance, the most well-known artistic expression of the New Negro movement. (Reiss also illustrated Alain Locke’s The New Negro, a groundbreaking anthology of essays, poetry, and music asserting black pride and creativity.) Leaders of the New Negro movement hoped that African American artistic achievement would help alleviate racial tensions in the 1920s. Although the Fisk University Jubilee Singers were received favorably by whites in Tampa, there is no indication that their performances had any impact on local race relations.

Objects and ephemera from “When the Train Comes Along”: Booker T. Washington at the Tampa Bay Casino, March 19-December 23, 2021

FURTHER READING:

Elsa Barkley Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom,” Public Culture 7:1 (1994), 107-146.

David H. Jackson, Booker T. Washington and the Struggle against White Supremacy: The Southern Educational Tours, 1908-1912 (2008).

James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosemond Johnson, The Books of American Negro Spirituals, including The Book of American Negro Spirituals and the Second Book of Negro Spirituals (1925)

Alain Locke, ed., The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925).

Written by Dr. Charles McGraw Groh and Dr. Rodney Shores. Learn more about music and community memory with their presentation, "Music and Memory: The Role of Spirituals in Booker T. Washington's Florida Educational Tour".