“MR. SKINNER, AT YOUR SERVICE”

The Labor of Fine Dining at the Tampa Bay Hotel

This online exhibit is adapted from a 2017 panel exhibit of the same name created by students at The University of Tampa and Dr. Charles McGraw Groh, Associate Professor of History.

INTRODUCTION

Between 1891 and 1932, sumptuous feasts and impeccable service helped define the Tampa Bay Hotel as one of the country’s most lavish resorts. Join us for a rare look behind the scenes of the hotel’s opulent dining room and the men and women responsible for its epicurean delights.

MEET MR. SKINNER

Oscar E. Skinner (standing, second row, right) with Executive Staff, 1905, Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Oscar E. Skinner (standing, second row, right) with Executive Staff, 1905, Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

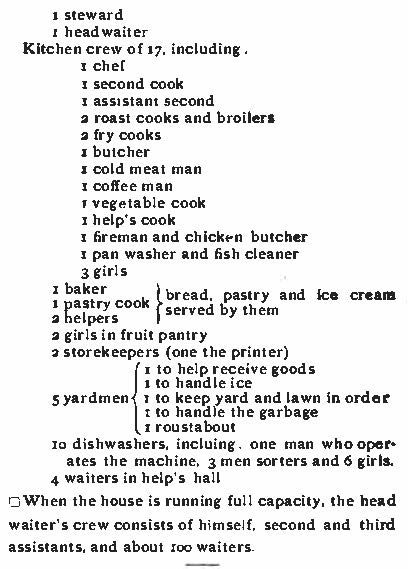

Manager David Lauber recruited Oscar E. Skinner to join the executive staff of the Tampa Bay Hotel for its 1905-1906 winter season. Although he was still in his early twenties, Skinner assumed the enormous responsibilities of the hotel steward. Skinner purchased provisions, maintained kitchen account books and storeroom inventories, and supervised the complex hierarchy of kitchen and dining room workers:

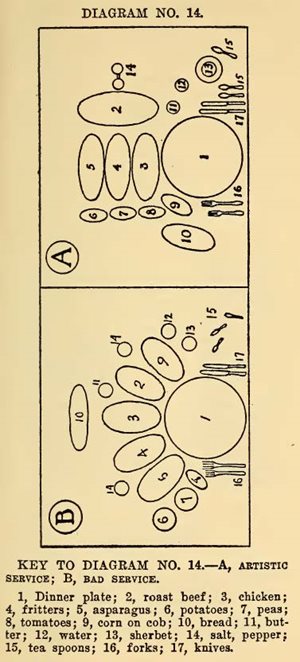

Image from John Tellman, The Practical Hotel Steward (1900).

Image from John Tellman, The Practical Hotel Steward (1900).

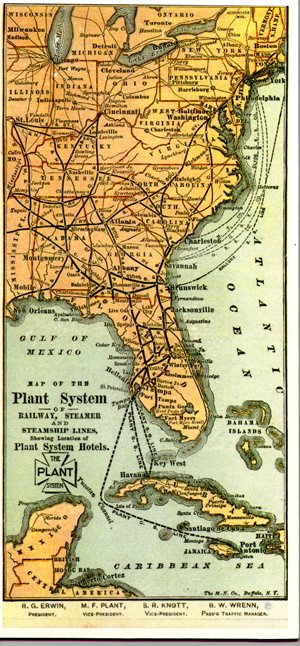

Seasoned Travelers

The extension of the railroad into Florida allowed hotel workers to maintain year-round employment by migrating seasonally between summer and winter resorts. The design of summer resorts in New York and New England differed dramatically from the exotic Moorish architecture of the Tampa Bay Hotel, but elite travelers found continuity in the services provided by the expert staff.

Map from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Map from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

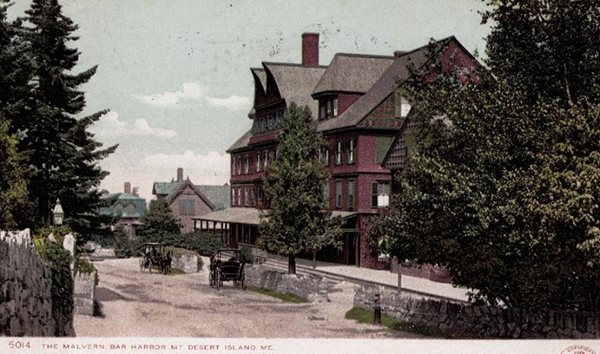

In January of 1891, George W. Harding, the Tampa Bay Hotel’s first headwaiter, brought more than fifty waiters from the Malvern Hotel to staff the dining room of Henry B. Plant’s luxurious new resort. Constructed in 1882 as an “old English Inn,” the Malvern charmed summer visitors to Bar Harbor, Maine. Additions to the Queen-Anne-style structure complemented the beauty of the natural landscape. Sadly, fire destroyed the hotel in 1947.

Postcard courtesy of Bar Harbor Historical Society.

Twenty-five kitchen assistants accompanied Chef Joseph P. Campazzi from Coney Island’s Manhattan Beach Hotel in 1891 to inaugurate fine dining at the Tampa Bay Hotel. The Manhattan Beach Hotel, completed in 1875, had several rustic elements that blurred the boundaries between the buildings and the boardwalk. Ultimately, the beachfront property became too valuable to residential developers, and the resort was torn down in 1911.

Postcard courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library.

.png.aspx;)

Top Chefs

Kitchen.jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=357) Jules E. Bole (second from left) with Kitchen Staff, 1905, Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Jules E. Bole (second from left) with Kitchen Staff, 1905, Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

The chefs at Florida’s resort hotels enjoyed a level of national acclaim that rivaled the celebrity of even the most well-known guest. In 1905, Jules E. Bole took a break from his post at St. Louis’ Hotel Jefferson, where his extravagant repasts had impressed the foreign dignitaries and other notables who attended the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition. He accepted an invitation to create the culinary masterpieces that would distinguish the Tampa Bay Hotel’s winter season.

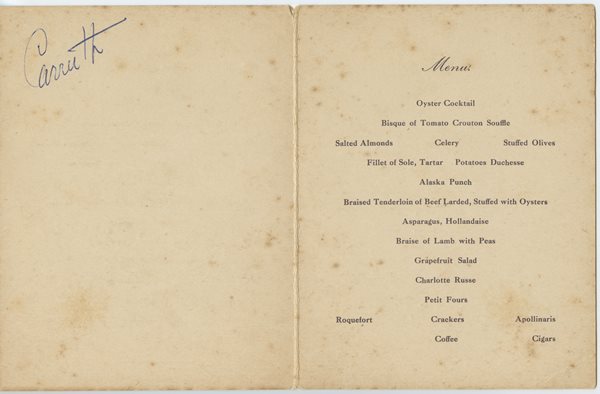

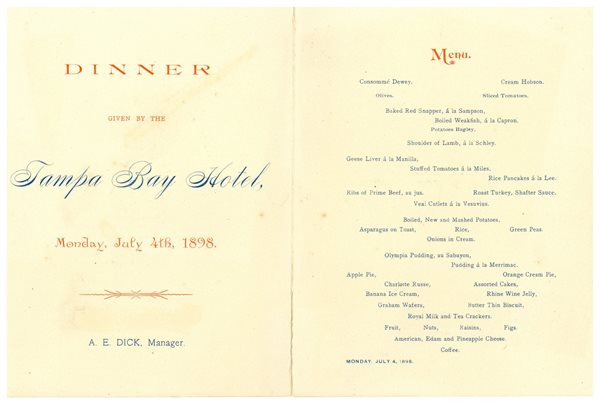

Menu from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Menu from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

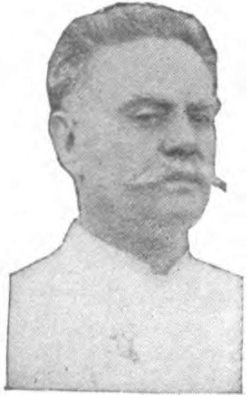

Joseph P. Campazzi, the Tampa Bay Hotel’s first chef, was also its most famous one. He rose to prominence as a private cook, serving the imperial household of Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro II and later New York governor Samuel J. Tilden. In 1885, while in residence at New York’s Murray Hill Hotel, the Italian-born chef catered the inaugural ball of President Grover Cleveland. Campazzi had the distinction of being the first chef at both Henry Flagler’s Hotel Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine, Florida, and Henry B. Plant’s Tampa Bay Hotel.

Photograph from A.C. Hoff, Roasts and Entrees of the World Famous Chefs (1914).

Photograph from A.C. Hoff, Roasts and Entrees of the World Famous Chefs (1914).

Chef Campazzi worked all over the globe, but the tragic death of an infant child while he and his wife were in Tampa created a permanent tie to the Cigar City. Ruth Campazzi was buried in Oak Lawn Cemetery.

CONFECTIONS

Although they did not attain the level of celebrity enjoyed by chefs de cuisine, bakers and pastry chefs played a vital role in maintaining the reputation of seasonal resort hotels. Steward Oscar Skinner knew that guests would lodge complaints over flavorless bread, no matter how extravagant and delicious they found the rest of the meal.

Kitchen.jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=419)

Oscar Skinner (seated) with Bakery and Pastry Staff, 1905, Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Born in Hamelin, Germany, Edward Spohr achieved success as a pastry chef in the United States. He spent multiple seasons traveling between the Tampa Bay Hotel and New York’s Long Beach Hotel. Spohr thrived in an environment that overwhelmed other confectioners. Unlike year-round hotels, where the painstaking work of baking and candy making took place in a separate location, resort hotels confronted the bakery and pastry staff with the kitchen’s bustle and the demands of waiters.

.png.aspx;)

The Wait Staff

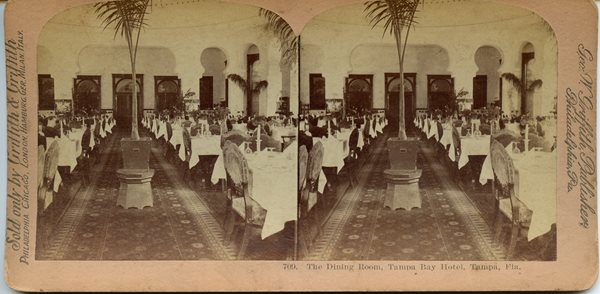

Stereoscope card from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

In the late nineteenth century, European convention held that only men could provide the flawless service that defined fine dining. American hotel managers agreed, and they frequently chose black men to wait tables in the country’s most elegant dining rooms. The growing African American population in cities like New York guaranteed a steady labor supply, and status-conscious elites associated black labor with a romanticized image of southern plantation slavery. Florida resort hotels went even further in exploiting this connection, requiring waiters to perform in minstrel shows and cakewalks for the amusement of guests.

.jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=293)

Photograph courtesy of Leslie’s Weekly, April 7, 1898, p. 214.

Pictured above, waiters performed as the “Tampa Bay Hotel Quartet,” one of the hotel’s most popular entertainment offerings throughout the 1890s. These productions showcased the singers’ vocal talents and mastery of contemporary standards, but the waiters were also forced to act out the racial stereotypes that characterized vaudeville minstrel shows. Whatever their own feelings about these representations, dining room workers used minstrel shows to raise funds for sick and elderly waiters.

Photograph courtesy of Leslie’s Weekly, January 5, 1899, p. 16.

Black waiters teamed with local women to stage the cakewalks that became popular attractions at Florida resort hotels. Decked out in their best dress, couples competed in a stylized walk with improvised movements and gestures for a prize, usually a cake. Hotel managers encouraged black waiters to exaggerate their movements to conform to racial stereotypes, but dancers could also use their performance to poke fun at elite, white pretensions.

.jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=339)

Photograph of Tampa Bay Hotel bellmen with Henry and Margaret Plant, Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Tampa Bay Hotel porters and bellmen helped waiters stage athletic events on the hotel grounds for the entertainment of guests. The practice mimicked the successful relationship Henry Flagler had established with the Cuban Giants, the country’s first black professional baseball team. Supplementing their income by waiting tables at Flagler’s Hotel Ponce de Leon, the Giants trained and competed each winter in St. Augustine. In 1908, Tampa Bay Hotel waiters fielded their own baseball team to compete against the Tampa Grays.

.png.aspx;)

COMMANDERS OF THE DINING ROOM

In 1905, steward Oscar Skinner watched as a white headwaiter took charge of the Tampa Bay Hotel’s dining room for the first time, commanding its staff of black waiters. Across the United States, African American men faced increasing competition from European immigrants for the most prestigious hotel job available to men of color. In response, black headwaiters created new labor organizations, authored columns in black-owned newspapers, and even wrote training manuals to improve professional standards and resist the period’s rise in employment discrimination.

Image from John B. Goins, The American Waiter (3rd ed., 1914).

Image from John B. Goins, The American Waiter (3rd ed., 1914).

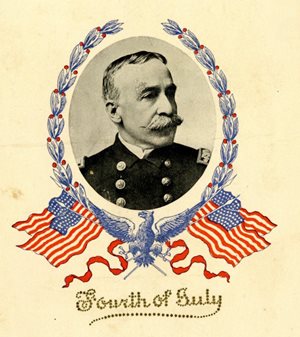

Born a slave in 1842, Wilson Percival ascended the ranks of hotel service to become one of the leading headwaiters in the nation. From 1892 to 1901, Percival migrated seasonally between West Babylon, New York, and Tampa, enjoying the longest tenure of any headwaiter at the Tampa Bay Hotel. Each winter, he mailed copies of menus, like the one pictured below, to be published in the Babylon newspaper.

Menu from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Menu from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Wilson Percival and Henry McKenney, headwaiter during the Tampa Bay Hotel’s 1903 season, also achieved success supervising the dining rooms of Henry Flagler’s east coast resorts. Percival served multiple years as headwaiter at the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach, and, in 1908, he took charge of the wait staff at St. Augustine’s Hotel Alcazar. Although white headwaiters succeeded in supplanting their black rivals at the Tampa Bay Hotel in 1905, African American men remained hotel headwaiters in Palm Beach through the 1920s.

-(2).jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=379) Rathskeller image from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Rathskeller image from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

German immigrant Charles Fortman spent five seasons working at the Tampa Bay Hotel, beginning in November 1906. After a year as the assistant headwaiter, Fortman was promoted to headwaiter, and, still later, his brother Joseph managed the bar in the Rathskeller. Like Percival, the siblings spent months of the year away from their families, but they formed strong friendships in Tampa. In 1912, word reached the Cigar City that 32-year-old Charles had died of pneumonia in his Philadelphia home.

A Woman's work is never done

In 1913, the Tampa Bay Hotel began employing waitresses in place of waiters, although men still held the dining room’s supervisory positions. For the next eighteen years, young, white women migrated seasonally between the Tampa Bay Hotel and the Lake Tarleton Club in Pike, New Hampshire.

.jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=478)

Photograph of 1927 Kiwanis Club banquet courtesy of Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System.

The years leading up to World War I had seen the most fashionable travelers bypass the Cigar City in favor of Palm Beach resorts. In response, Tampa Bay Hotel managers reoriented the hotel toward businessmen and the new middle-class “vacationer.” Hotels that catered to these markets were expanding rapidly across the country, and some experimented with employing women to staff their dining rooms. Proponents of female labor perceived women to be more obedient and willing to work for less pay than men.

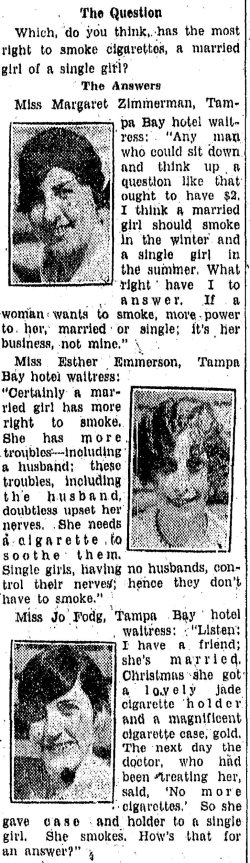

Tampa Morning Tribune, March 9, 1928.

The employment of young, white women as waitresses, secretaries, and salesclerks constituted the largest sector of job growth in the United States between 1890 and 1930. Women wrestled with the mixed messages they received from parents, advertisers, and coworkers in the new mixed-sex workplace. Bobbed hair, shorter hemlines, and cigarette smoking were all signs of changing social mores. Waitresses found that they risked rebuke or even firing if they went too far, as Evelyn Bishop discovered when she wore pants in downtown Tampa.

.jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=476)

Photograph from Henry B. Plant Museum collection.

Fifteen-year-old Evelyn Bishop accompanied her mother Alice, a hotel housekeeper, from New Hampshire to Florida in the 1920s. The promise of employment as a Tampa Bay Hotel waitress was tempered by low wages, and she was sometimes treated poorly by haughty guests. Bishop found solace in the support of coworkers and the possibility of romance. In 1929, she married Tampa Bay Hotel chauffeur Winfred Zealor.

Further Reading

Brooke Baldwin, “The Cakewalk: A Study in Stereotype and Reality," Journal of Social History 15:2 (Winter 1981), 205-18.

Dorothy Sue Cobble, Dishing it Out: Waitresses and the Unions in the Twentieth Century (Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1991).

A.K. Sandoval-Strausz, Hotel: An American History (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2007).

David S. Shields, The Culinarians: Lives and Careers from the First Age of American Fine Dining (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2017).

This exhibit was researched by Dr. Charles McGraw Groh and curated by the following University of Tampa students:

Zachary Adams, Nola Berish, Josie Bready, James Hackett, Christopher Hendrix, Adam Irvine, Christopher Kelly, Olympia Kledaras, Thomas Krupinski, Xavier Lockley, Taylor McCullough, Melissa Micerri, Nicholas Rivera, Sean Spratt, Nicholas Starkman, Alexzandra Velez, and Karl Walls.