Minstrelsy in Black and White

Tenor Dylan Glover appears as the real-life singer/songwriter Bert Leighton, performing the 1910 popular hit “Steamboat Bill.” Dr. Rodney Shores provides piano accompaniment. (Videographer: Troy Cusson)

SYNOPSIS

The lyrics of “Steamboat Bill” tell a fictional tale, but the story is based on a real event. In 1870, the Robert E. Lee beat rival steamboat the Natchez in a race down the Mississippi. The song became the most successful hit written by Bert Leighton and his brother Frank. “Steamboat Bill” would later appear in the Disney cartoon classic Steamboat Willie, and it inspired the Buster Keaton film Steamboat Bill, Jr.

MINSTRELSY AT THE TAMPA BAY CASINO

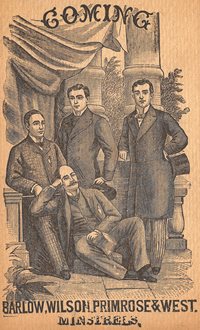

Barlow Minstrels Advertising Card, Private Collection

As part of the Barlow Minstrels, Bert Leighton made multiple appearances at the Tampa Bay Casino around 1900, frequently alongside his ragtime song-and-dance partner Walter Wilson. White minstrelsy had evolved significantly in the preceding decades as performers faced competition from variety shows, musical comedies, and even African American minstrel shows. Although they did not entirely abandon blackface makeup and songs romanticizing plantation slavery, minstrel troupe owners increasingly relied on entertainers like Leighton to provide more “refined” entertainment. Leighton later recounted that, as they toured southern states, he, his brother Frank, Wilson, Hughey Cannon, and John Queen frequented local black performance venues. Each would go on to success in vaudeville and as popular songwriters by borrowing from African American folk songs.

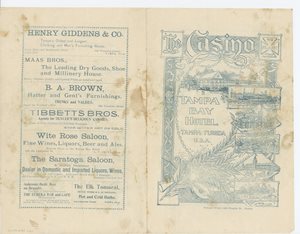

Richard and Pringle’s and Rusco and Holland’s Big Minstrel Festival, Tampa Bay Hotel Casino Program, January 27, 1899, Henry Plant Museum Archives

Black minstrel companies provided one of the few paths to commercial success for African American musicians and entertainers in this period. Claiming to be ex-slaves, black performers could assert authenticity in their staged representations of prewar plantation life. Unfortunately, this premise prevented them from straying too far from white-created stereotypes. The Georgia Minstrels enjoyed great popular success, but they were unable to avoid their troupe being purchased and managed by whites. Appearing at the Tampa Bay Casino in 1899 as part of Richard and Pringle’s and Rusco and Holland’s Big Minstrel Festival, they stretched the boundaries of possibility by incorporating jubilee songs and other forms of black religious music. Their mixed reception in Tampa revealed that performers who did not uphold plantation caricatures risked being perceived as uppity by white audiences.

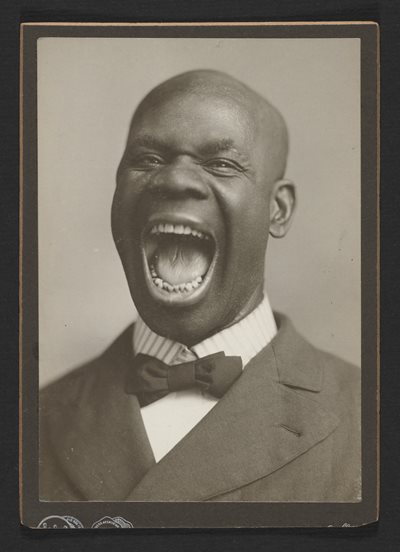

Billy Kersands, Harvard University Library

Appearing at the Tampa Bay Casino as part of the Big Minstrel Festival, Billy Kersands was the highest-paid black entertainer in the country. Known for his ability to contort his mouth into exaggerated expressions and to stretch it to fit several billiard balls, Kersands carefully acted out his assigned role as a dim-witted black man. Nevertheless, Kersands was embraced by black as well as white audiences, since his original song compositions remained firmly grounded in slave work songs. Black listeners discerned subtle critiques of slavery and racism that were not heard by whites. Kersands made a permanent mark on popular culture by inventing the character of Aunt Jemima in one of his songs.

FURTHER READING:

- Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895 (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2009).

- Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.)

- M.M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (Univ. of Virginia Press, 1998).

- Peter C. Muir, Long Lost Blues: Popular Blues in America, 1850-1920 (Univ. of Illinois Press, 2009.)

- Robert C. Toll. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in 19th Century America. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974).

Written by Dr. Charles McGraw Groh. Learn more about the history of popular entertainment in his presentation,

"Plant's Follies: The Casino and Tampa's Civic Identity."