Dirty Laundry: True Tales of Women Workers at the

Tampa Bay Hotel

This online exhibit is adapted from a 2019 panel exhibit of the same name created by history students at The University of Tampa and Dr. Charles McGraw Groh, Associate Professor of History.

INTRODUCTION

In the early twentieth century, social reformers and popular magazines such as

True Story,

True Confessions, and

Dream World discovered the working woman. Industrialization created an unprecedented demand for new workers in the country's burgeoning service sector. In response, large numbers of young, white women journeyed far from parental supervision in search of self-support or to contribute money to their families. They joined established female wage-earners, especially African American women, for whom service work had long been a necessity. This exhibit showcases the lives of one group of female wage earners, the housekeepers, maids, and laundresses who labored at the Tampa Bay Hotel. Their stories reveal the opportunities, dangers, and constraints that accompanied the dramatic expansion of women's paid labor between 1890 and 1930.

Dream world

Popular magazines assumed that a loving marriage was every working girl’s “dream world.” In reality, as occupational and educational opportunities for white women expanded, a substantial minority preferred to remain single, sometimes permanently, and to focus their aspirations on careers.

.jpg.aspx;?width=400&height=548) Bertha Maser and Executive Staff, 1905, Henry B. Plant Museum Collection.

Bertha Maser and Executive Staff, 1905, Henry B. Plant Museum Collection.

Starting as a maid at the Planter’s Hotel in St. Louis, Bertha Maser climbed the ranks to become the housekeeper of two seasonal resorts, the Tampa Bay Hotel and Rhode Island’s Hotel Mathewson. As the Tampa Bay Hotel’s housekeeper between 1905 and 1908, Maser reported directly to the manager and even ran the hotel in his absence. By remaining single, Maser could relocate to accept increasingly prestigious positions, including the Hotel Seminole and the Hotel Astor. In 1942, she became one of the country’s few female hotel managers. Click on the map to track Bertha Maser's career advancement.

.jpg.aspx;?width=400&height=568)

Atlantic Coastline Railroad Map 1929, Touchton Map Library, Tampa Bay History Center

The Salisbury, located at Fifth and Warren avenues, also announces its opening. Bertha T. Maser, formerly connected with Hotel Astor and Roosevelt, New York City, is the manager of this hostelry.

The above quote is from the Spring Lake Gazette, June 25, 1942, page 1.

TRUE ROMANCES

Philomena Oakes, HP Collection

When they had any choice over their occupation, white women preferred jobs they considered respectable and with some opportunity to meet a husband. Philomena Oakes, a laundress, became the first of many Tampa Bay Hotel employees to wed a coworker. She wed William Yancey, the laundry manager, on July 4, 1891.

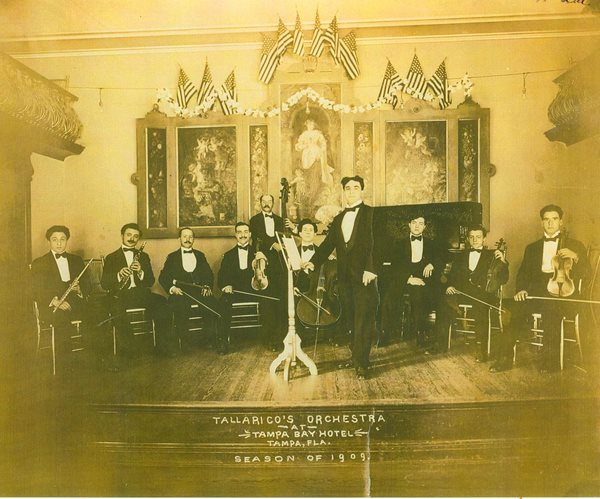

Tampa Bay Hotel Orchestra, HP Collection

The migration of workers between seasonal resorts fostered a close-knit culture, defined by practical jokes and romance. Young women and men were “agog with anticipation” after housekeeper Bertha Maser announced an employee ball to be held at the Tampa Bay Hotel Casino to celebrate the end of the 1908 winter season.

Music was furnished by the Tampa Bay Orchestra and the members showed the pleasure which they felt at giving enjoyment to the fellow employees at Tampa’s noted hostelry.

The above quote is from the Tampa Tribune, March 10, 1908, page 12.

TRUE CONFESSIONS

Tampa Bay Hotel Room, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System

Unlike the simple manager-worker relationship that defined men’s jobs in manufacturing, the new service economy featured a more complex exchange between workers, managers, and customers. In grand hotels, housekeepers and lady guests both had the power to make life difficult for the chambermaid, but she could sometimes play off one against the other.

Unless she is shrewd and sharp she is apt to cause trouble for herself and for the housekeeper, without in the least intending to do so, by simply repeating in one room what she sees and hears in another.

The above quote is from Mary Bresnan, “Chambermaids as Ladies’ Maids,” The Practical Hotel Housekeeper (1900), pages 8-9.

In 1909, Tampa Bay Hotel Manager David Lauber began offering the services of ladies’ maids to unaccompanied female guests. The maid carried and unpacked luggage, assisted guests in dressing, and ironed garments. Such intimacy facilitated the exchange of gossip, a development that no doubt worried Virginia Bellows, the new housekeeper.

TRUE DETECTIVE

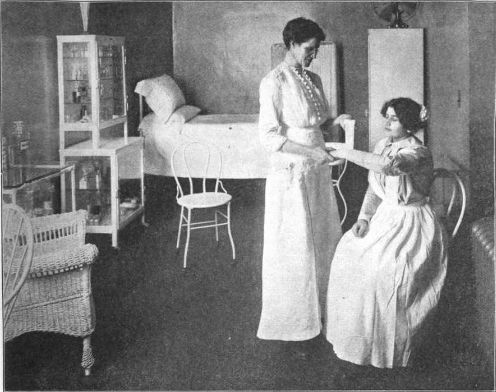

The expansion of young, white women’s employment prompted anxiety in American society. Progressive reformers joined social workers in investigating hotels to improve employee health, safety, and morals. In the photo below, an infirmary was added to the Hotel Astor during the tenure of housekeeper Bertha Maser, a former executive of the Tampa Bay Hotel.

Harper’s Weekly, January 17, 1914, p. 9

Employment as a Tampa Bay Hotel maid promised Fannie Kersey a new start after she left her abusive husband in 1914. Following her to Tampa, Benjamin Kersey had no difficulty gaining access to the servants’ quarters, where he attacked her. Fortunately, two maids came to her aid, and he was soon apprehended by police.

It is much safer for two girls to work together than have one lone girl at eleven or twelve o’clock at night going through long deserted halls to put a room in order.

The above quote is from Mary Bresnan, “Night Work,” The Practical Hotel Housekeeper (1900), page 51.

TRUE EXPERIENCES

.jpg.aspx;?width=600&height=463)

Tampa Bay Hotel Laundry, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System

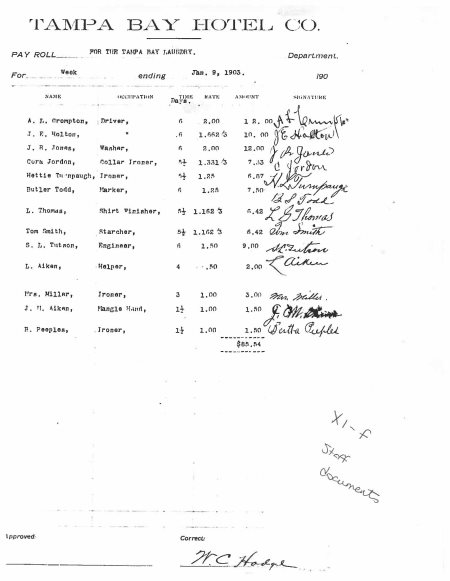

The mixed-sex workplace was a product of the new service economy. White men worked alongside black and white women in the original Tampa Bay Hotel Laundry, which serviced the Plant System Railroad as well as the seasonal resort. The men earned higher wages and promotions. After purchasing the Tampa Bay Hotel in 1904, the city closed the year-round laundry. Instead, the hotel operated a seasonal laundry service for hotel guests. A smaller number of local black women staffed the new department, and they received significantly lower pay.

Payroll, HP Collection

Wanted—Good colored women to do washing and ironing. Apply to Housekeeper, Tampa Bay Hotel.

The above quote is from the Tampa Tribune, January 11, 1906, page 7.

TRUE STORY

Julia Cotton, HP Collection

Julia Cotton worked occasionally as a kitchen maid at the Tampa Bay Hotel. She preferred, though, to earn money away from the hotel by taking in laundry at home. Home-based laundry businesses offered black women their greatest chance of achieving economic independence in turn-of-the-century Tampa.

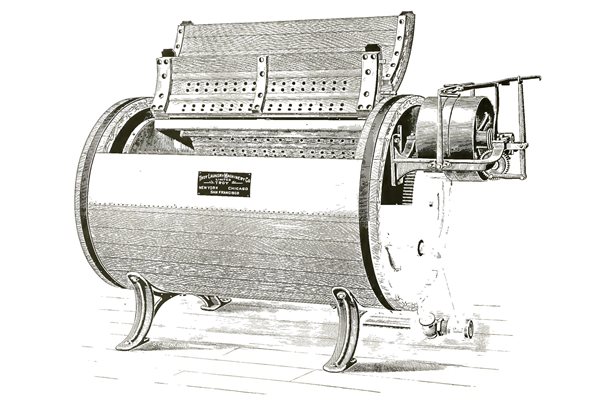

Laundry Cylinder, Troy Laundry Machinery Co. Catalog (1891), p. 4.

The rise of commercial laundries with specialized equipment pushed many black women out of business. The original Tampa Bay Hotel Laundry advertised to the public, making it a direct competitor of local laundresses. Like many of the black women who could not find jobs at the new commercial establishments, Cotton was forced into domestic service. Her experience offers the potent reminder that the expansion of service-sector employment in this period offered new job possibilities to some women while reducing opportunity for others.

J.R. Cooley, who has managed the White Star Laundry for the past two years, will on July 21st assume management of the Tampa Bay Hotel Laundry…. The patronage of the general public is solicited.

The above quote is from the Tampa Tribune, July 18, 1902, page 7.

Further Reading:

Susan Porter Benson, Counter Cultures: Saleswomen, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890-1940 (Univ. of Illinois Press, 1986).

Ileen A. DeVault, Sons and Daughters of Labor: Class and Clerical Work in Turn-of-the-Century Pittsburgh (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1990).

Nancy A. Hewitt, Southern Discomfort: Women’s Activism in Tampa, Florida, 1880s-1920s (Urbana: Univ. of Illinois, 2001).

Tera W. Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1997).

Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 1986).

This exhibit was researched by Dr. Charles McGraw Groh and curated by the following University of Tampa Students:

Shae Donaldson, James Gallatin, Taylor George, Dominique Goden, Elizabeth Ho Sing-Loy-Keller, Bridget O’Toole, Eva Pagan, Erica Ragan, Samantha Richter, Jackson Sanger, Jacqueline Spolidoro, Brady Thompson.